Directing, Sensitively

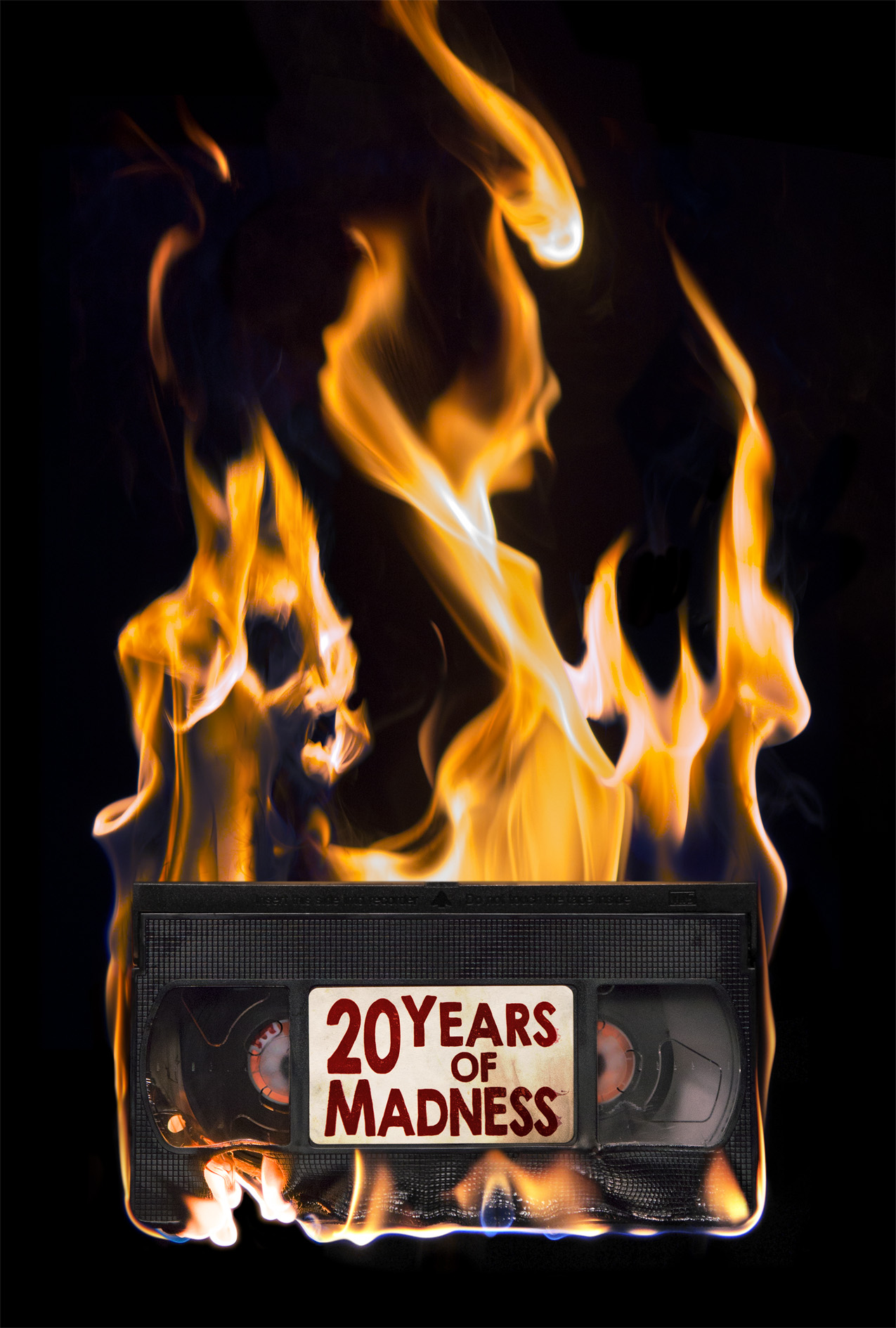

Addictive Personalities: 20 Years of Madness Explores Friendship, Filmmaking and Mental Illness

by Kelly Leow | April 1, 2015

Originally published on moviemaker.com, archived link here.

“If there’s anything else in life that you can do and be happy with, go do that. Because this is the most difficult path you can take,” says Jeremy Royce, director of feature documentary 20 Years of Madness. “But we’re all addicts.”

“There is a sense of being called,” agrees Jerry White Jr., Royce’s co-producer and chief subject. “Of not having a choice, ultimately.”

Royce: “I can never go back at this point. It’d be like meeting the love of your life, and then breaking up, and for the rest of your life knowing that they’re out there still.”

The pair are talking about—what else—moviemaking. That the art can be both curse and redemption—in short, madness—is a central idea in 20 Years of Madness, a film propelled by all manner of irrational forces: heady emotions, gloriously untethered creativity, and the ironic hand of fate.

I meet Royce and White at the Treasure Mountain Inn in Park City, Utah, late January, where their film has just premiered at the Slamdance Film Festival (it goes on to pick up Jury Honorable Mention for Documentary Feature). The premiere and award are a career peak for both filmmakers, though one that comes on the tail of years of professional and emotional strife—the cause for Royce and White’s complicated relationship with filmmaking.

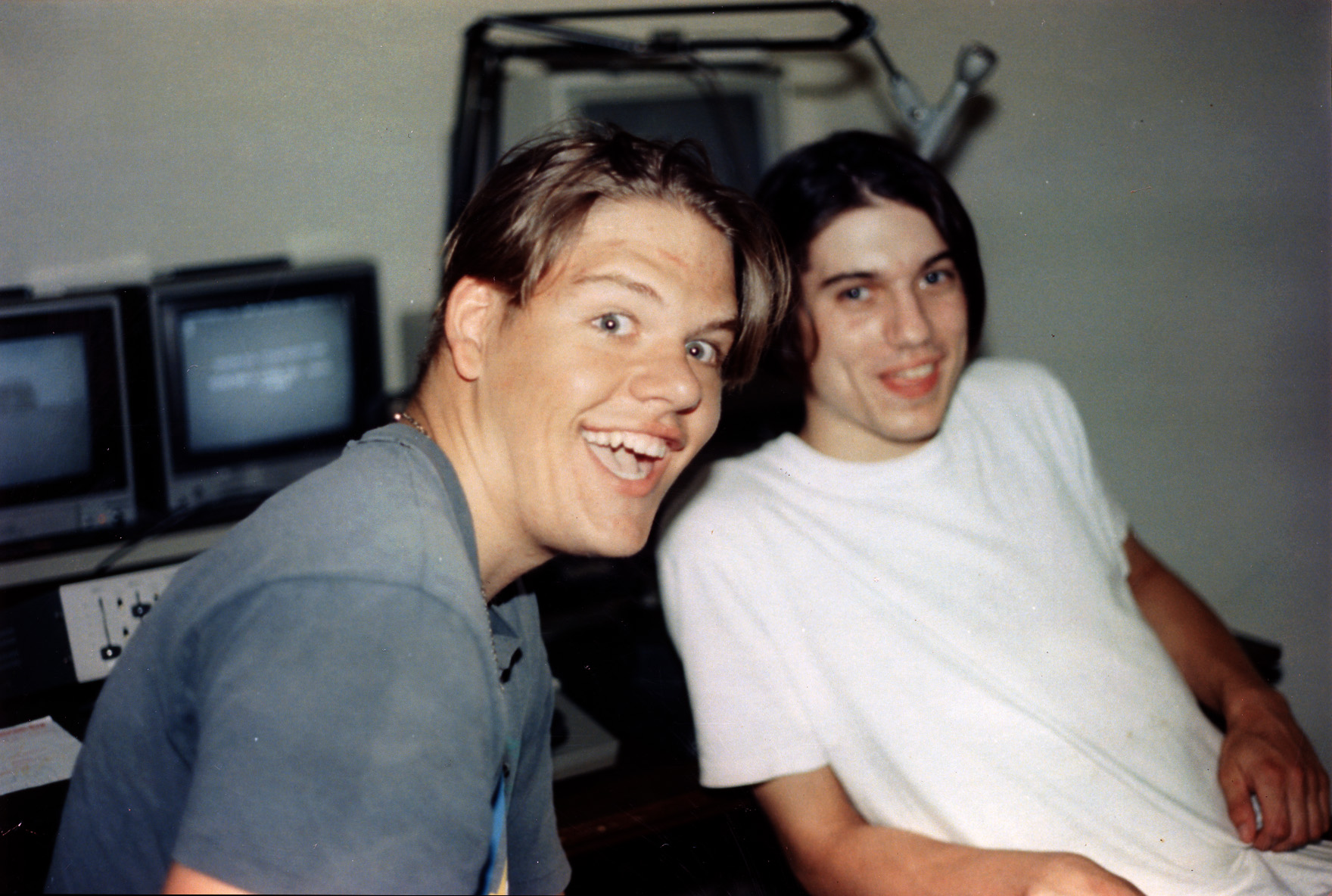

Royce fell into making 20 Years of Madness after getting to know White, his USC film school roommate. In mid-’90s Detroit, the teenaged White had led a gang of high-school friends—misfits, theater kids, Goths, charged by a unconventional wit, an explosive youthful energy and the stick-it-to-the-man rage of the recently canonized Kurt Cobain—in producing the public access television show 30 Minutes of Madness. After 14 episodes, the group dissolved through a series of fallings out, in particular the fracturing relationship between White and best friend Joe Hornacek. Now, two decades after 30 Minutes of Madness’ original run, the former friends—activated by White, documented by Royce—reconvene to make one last episode of the show that anchored their teenaged lives.

The richness of the subject matter lent itself to certain structural conceits. “[The group] had documented getting to know each other the first time around,” says Royce, “and now they’re going through that same exact process again—a direct reflection of the entire history of the show, recreated in the span of a month.”

On one level, 20 Minutes of Madness is a post-mortem, investigating the lifespan of both the show and of a certain kind of teenaged friendship, the kind that feels like it could never end. 30 Minutes of Madness was weird and original and—if you believe Royce’s doc—actually pretty good, a collection of comedy sketches that, with their manic non sequiturs, free-associative cultural commentary and amateur in-camera effects, contained flashes of SNL, John Waters, Monty Python and Liquid Television. (The show’s spiritual descendents include such touchstone American comedies as Jackass, Robot Chicken and Mr. Show with Bob and David). White estimates that the original viewership was “150,000 homes” in Oakland County, Michigan (“but it was all pre-Internet so I never got a great sense of it”). Its makers fervently—probably naively—believed that the show could one day take off on a major network like MTV. So how and why did they let it die?

Another question the film poses—the one that, at least initially, piqued Royce’s storytelling sense: Was it the crazy of its creators that made 30 Minutes of Madness, or 30 Minutes of Madness that made its creators crazy? Royce’s and White’s talk of addiction, heartbreak and other psychological maladies isn’t just figurative—30 Minutes’ cast, now in their late 30s, have seen more than their fair share of trouble. Some are unemployed, some homeless; others, like musician John Ryan, struggle on and off with substance abuse. Many, like Hornacek, have been diagnosed with some sort of mental illness. Of the 16 people who participate in the doc, the financially and psychologically well-adjusted are few and far between.

White himself hasn’t entirely escaped adulthood’s degradations. Though he always wanted to direct, he met with all the usual roadblocks on a roundabout journey to his current career, crewing on productions in Los Angeles. 20 Years sums White’s young-adulthood up with an efficient, and poignant, device: clips from a series of “video memoirs” White makes every birthday—“my state of the union for myself,” he says. From the age of 19 onwards, his “This is me at [age]” montage charts changes both mundane and dramatic: one year he’s in Germany, another he’s in Japan teaching English; one year he’s applying to grad school, then rejected, then busy at work at USC. It’s a curve of optimism, depression, and renewed optimism, and plays all too familiarly to anyone who’s indulged in grandiose dreams of being an artist, only to have to scale them down, and down again.

The Time Traveling Powers of Friendship

White gave full access to Royce to use these birthday videos, though he himself hasn’t watched any of them yet. Royce also dove into the “300 or so hours” of footage that White had kept, and diligently digitized, since the ’90s—not just material for 30 Minutes, but hours and hours of personal footage: kids hanging out, expounding on their views on life.

In more than one prescient moment, the young White asks his friends to predict where they’d be as adults; the answers range from eerily accurate to heartrendingly misguided. Royce deploys these clips as a motif throughout his film.

“Jeremy had this great idea of using the archival footage to comment on different moments in the present day. It’s much like [Michael Apted’s] Up series or [Jonathan Caouette’s] Tarnation, which are touchstone films for us,” says White. “You have these people young and full of dreams, talking about the future, and then you cut to them now.”

The way friendship factors into a life over time is the major theme of 20 Years of Madness. While the group’s closeness provided a safe space for 30 Minutes’ remarkably unself-conscious skits (including one where John Ryan plays a tantrum-throwing infant), it also ended up rubbing unproductively against said creative process—and 20 years later, the same happens.

Hornacek and White’s disastrous late-teen rift is presented as the crack that splintered the entire endeavor, though the intricacies of the falling out are a little vague (perhaps Hornacek’s spirituality clashed with White’s single-mindedness; perhaps things simply got too rivalrous). When the two reunite with their cohorts for the first time in years, everyone’s edges seemed to have, for the most part, smoothed over.

Yet old patterns within the group cast shadows over the present in the form of buried resentments and jealousies, which threaten to boil over the month-long new shoot. Coordinating everyone’s schedules over the course of a month is a constant challenge, which exasperates White to no end. His USC-honed directorial technique jars some of his cast, like Ryan, who complains that “having a script doesn’t leave as much room for collaboration.” Shouting matches take place between White, Ryan and fellow cast member Jesus Rivera, who feels like White sees his cohorts not so much as equal collaborators, but as “puppets.” Within this volatile mix of personalities the threat of mutiny looms large, as White tries to restrain his possessive tendencies.

A layer of guilt, too, underpins many of the group’s new interactions—in times of individual need, “we all walked away,” says White during a private conversation early in the film. As he tells me at Slamdance, “There’s a certain amount of personal responsibility for no longer being a part of a support network for friends who have slipped through the cracks.”

In granting Royce access to his life history, White—vibrantly charismatic but with a temper—agreed to be depicted in a less-than-flattering light. Indeed, gaining the trust of all his (often bitterly honest) subjects was crucial for Royce. He encouraged input from many of the film’s primary characters, including Ryan and Hornacek. The finesse this required, the director says, was worth it—“all these people are exposing really personal things that they’ve never spoken about in public before, so I felt a lot of responsibility to keep them involved. The last thing I want to do is to make someone struggling with mental illness feel like they’re being taken advantage of or exploited.”

The director did do a bit of creative facilitating, though: “creating spaces for moments” that he needed to play on camera, like the critical first reunion between White and Hornacek (now a carpenter living in Detroit). “I wouldn’t let them see each other until the crew was in town because I wanted to make sure we were documenting it.”

>He also made it clear whose film it was from the start: “The only way it was going to work was if I had full control over the final film. It couldn’t be a vanity project.” Yet Royce admits that his investment in the project wasn’t purely as an observer. “It may sound arrogant to think a documentary can have a positive effect—like I can have an effect, by making this film, on these people’s lives. But it was a goal of mine [to help] some of these people who are struggling.”

Editing began in August 2012, and didn’t wrap until August 2014—two years in which Royce poured over 500 hours of footage, both new and archival, almost entirely himself (“after six months, it was hard to pay someone else”). As much input as he received from White and co., Royce struggled to maintain his position as the most objective man in the room: “You get so close to it that you really have to create artificial breaks to get some space.”

Agony and Ecstasy

Despite the setbacks and the scars, 20 Years of Madness shows a group of friends whose deep affection for each other overrides time and difference—and results in a 15th episode they are all proud of. By the doc’s close, successful screenings are held, celebratory firecrackers are lit, emotional speeches and letters are delivered (one note, addressed to White from a cast member, says, “I’ve been locked in a day-to-day funk for years, and you have the key”).

“It felt seamless coming back together,” says White. “There were a few people I approached who just didn’t wanna be a part of it, so they weren’t there. But the people who agreed to it were really excited to have this chance to reconnect, and in the years since, a lot of those bonds that were reformed have continued to stick together.”

It’s a testament, he believes, to the ultimate power—the fulfillment and the thrill—of creating 30 Minutes of Madness together. “Some of my friends have really gone through tough things, but when we come together, we return to that place of fun and creativity. I feel really moved by the fact that the show had an effect on other people as well as on me. A lot of them are on their current paths because of the influence of the show, or it gave them the DIY spirit to do something different.”

Our conversation returns to the idea of filmmaking as a kind of primal urge, often in defiance of reason—a drug, and, with its healing powers, a lifeline as well. Royce, who has worked as both a documentary editor and cinematographer for years, empathizes perhaps more than he’d like to with his subjects: Like him, “a lot of these characters are living the life they have to live. There’s an interesting parallel between addiction and art.”

Speaking of devotion to an art form, what about both men’s decision to go to film school? White currently has “about $300,000” in student loan debt. “As someone who started making home movies with my friends, I embrace the DIY mode of filmmaking,” he says. “And for a long time I was like, ‘I’m not gonna go to film school.’ But I needed a place that could give me the craft, because I was often doing things in a made-up way. My experience at USC hasn’t replaced guerilla filmmaking for me—it hasn’t replaced even Robert Rodriguez’s 10-Minute Film School. It’s just more tools in my toolbox.”

Royce has a different take on it: “Often I hear people say, ‘If you don’t have rich parents, you shouldn’t go to grad school.’ For me, it was the exact opposite—by getting access to student loans I had the opportunity to do something that I wouldn’t have been able to do otherwise. I left home at 16; I’d been financially independent since before then. I’ve always worked two or three jobs. You don’t have time to go off and make a film for two or three years. And although 20 Years wasn’t a USC film, the format of going to school there gave me the flexibility to go and make this film on the side.”

Whether he has a choice in the matter or not, Royce wants to continue going as long as he can. “It’s tough. Every movie might be your last. But the success of being a filmmaker, for me, is that as long as I’m doing something—even if it’s for YouTube, or my personal website—I’m still doing something.”

“And able to share it with your friends,” says White. MM